THE LEORA LETTER

Boys will be boys…and girls will be sluts.

February 16, 2022

“Slut,” “hoe,” and “thot” are slippery and subjective terms

that can apply to any girl or woman, regardless of how they dress or behave. I shed light on slut-shaming—how and why assumptions about being “too” sexual are applied, the consequences for women, and the impact on everyone, regardless of gender.

Q&A with Abortion Onscreen Researcher Steph Herold

Slut-shaming matters because when people are dismissed as sluts and hoes, they are denied care and compassion in a variety of situations: when they are sexually harassed, sexually assaulted—and when they need an abortion. To my mind, you can’t truly understand what it’s like to face these experiences without understanding slut-shaming.

When I worked at Planned Parenthood, I regularly received emails and letters expressing opposition to abortion, saying that anyone who was pregnant and didn’t want to be had gotten themself into that situation and needed to be taught a lesson. This argument, in essence, is that a woman who has had heterosexual intercourse (consensually or not) without the intention to procreate is a slut or hoe who deserves to be punished—and, indeed, the words “slut” and “hoe” were used often.

We know that some religious communities promote this viewpoint. Popular culture has also often reinforced the idea that nonprocreative sex is deviant and deserving of punishment—if you are a woman.

But we can change the narrative, and a number of researchers are engaged in important work to do just that. At this precarious moment in the US, when access to safe, legal abortion is severely curbed in many states and may become outlawed entirely, regardless of what state you live in, we need more fact-based representations, and we need more empathy.

Steph Herold is a researcher in the Abortion Onscreen program at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health. Along with her colleagues Dr. Gretchen Sisson and Renee Bracey Sherman, she studies how abortion is portrayed on film and television and what those depictions can tell us about how our culture understands abortion. Herold and her team investigate questions like: How does television impact people’s knowledge and attitudes about abortion? How do racial stereotypes shape depictions of abortion? How have depictions of abortion changed over time?

Currently, Herold and her team are analyzing over 40 interviews they conducted with content creators (showrunners, writers, producers) to understand how they make decisions about including abortion in their plot lines. They also are getting ready to launch a national survey to better understand if and how watching multiple abortion plot lines influence attitudes.

Leora Tanenbaum: What role does slut-shaming play in representations of abortion in popular culture?

Steph Herold: Sex and abortion are inextricably linked, since abortion can be a consequence of sex, so of course slut-shaming is part of many onscreen abortion depictions. One consistent trend is that often certain types of characters get abortions – the “bad girls.” Rebellious Maeve on Sex Education is called a “cock biter” by her classmates, a nod to her reputation as sexually promiscuous. On Bridgerton, Mariana faces relentless criticism from her family about having sex outside the confines of marriage, and they work tirelessly to hide her pregnancy, a source of familial shame. On CLAWS, nail salon owner Desna scolds her employee Virginia, a former exotic dancer, for not using a condom, saying, “You [were] giving happy endings behind the steak and shake! Your little ass is a lot of things but clean ain’t one of them!” Taken together, these types of depictions link abortion with irresponsible sexual behavior, inviting audiences to judge these characters instead of empathize with them. Even though Maeve, Mariana, Virginia, and other characters like them may be sympathetic in many ways, they are absolutely slut-shamed by other characters on the show. We also see this trope of “bad girl gets the abortion” play out through omission; there are very few characters on television who are parenting at the time of their abortions, suggesting a dichotomy between “good women” who are mothers and “bad women” who seek abortions, a dichotomy that just doesn’t exist in real life. In the US, about 59% of people are raising children at the time of their abortions.

Many shows depict characters who are worried about what their parents or other loved ones will think of them for having sex, for getting pregnant, for having an abortion. On both Chicago Med and New Amsterdam episodes, for example, teenagers worry that their legal guardians will stop loving them if they knew about their sexual activities. Two recent movies, Never Rarely Sometimes Always and Unpregnant, follow teenagers who take extensive measures to make sure their parents don’t discover their pregnancies and abortions, fearing judgment and shame. These characters go through extraordinary efforts to conceal their abortions in an attempt to avoid slut-shaming.

Tanenbaum: Your research shows that fictional characters on American television who obtain abortions are not representative because they tend to be Whiter, younger, and with a higher socioeconomic status than real American women who have abortions. What are the implications of this break from reality?

Herold: There are many possible implications here. First, for people who have had abortions, seeing people who don’t look like them, who don’t have their lived experience of being Black or Latina or Asian or mixed, being a parent, of struggling to make ends meet, of working multiple jobs and going to school, or whatever combination of real life experience, can have a real negative impact. It can increase feelings of shame and isolation, a sense that people who look like you and have your life experiences don’t or shouldn’t have abortions. Of course, television and film aren’t the only places where these cultural messages permeate, but they are pretty powerful.

Second, these inaccurate portrayals of abortion may lead to a misunderstanding of who has abortions, why they have abortions, what it takes to get an abortion in the US. Because abortion is such a stigmatized issue, one that people don’t often talk about from personal experience, what we see represented on television matters, and might stand in as someone’s most personal exposure to a person seeking abortion care. If they see representations that suggest that it’s easy to obtain an abortion, that no one needs financial or logistical support in obtaining abortion, and that the majority of people who have abortions look or act a specific way, that may influence how audiences conceptualize abortion as a cultural issue and a political issue. Does seeing more teenage characters obtain abortions make audiences more sympathetic to anti-abortion parental consent laws? Does seeing more white characters obtain abortions make viewers more susceptible to racist tropes about declining white birth rates? Does seeing abortion portrayed as medically risky make viewers more likely to support anti-abortion laws claiming to increase abortion safety, when they actually decrease abortion availability? We don’t know—these are all research questions worth exploring.

Tanenbaum: Could more realistic portrayals of women who have abortions in fictional television programs have an influence on public opinion and public policy?

Herold: This is a great question, and the answer is: maybe. There’s a wide body of research on how television influences viewer attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, including on reproductive health topics issues, whether it’s sexual behavior (like condom use) or beliefs about childbirth. It’s a bigger leap to make the direct connection between television and public policy, but I think it’s safe to say that television can influence viewers' attitudes, and in turn, those viewers may bring those attitudes to bear in the voting booth. When it comes to abortion specifically, we just don’t have many studies on the impact of television viewing – that’s something my team is working on right now. In 2021, we published a study looking at if and how a specific episode of Grey’s Anatomy, with an abortion plot line, impacted viewer attitudes about abortion. In this episode, a character named Cassie first tries to self-manage an abortion with herbs she purchased on the internet, and when this fails, she obtains a medication abortion from the hospital. We found that people’s knowledge of medication abortion significantly increased after watching the episode, but their support for abortion in general didn’t. To me that suggests that the implied causality – e.g., more abortion plot lines = more political change – is faulty, and the reality is more nuanced. It really depends what people are seeing on screen, what messages they’re taking away from that, how often they’re seeing these abortion plot lines, and if they retain any of the information for longer than the duration of watching the show. All of this is to say that television may have some effect on public policy and public opinion on abortion, and we’re still working to understand what that is.

Tanenbaum: What is one thing you wished more Americans knew about abortion? How can we get this across?

Herold: Abortion is unique among American cultural, political, and personal issues for many reasons, chief among them that knowledge, data, and facts don’t necessarily change how someone feels or thinks about abortion. So I’m not sure that there’s one thing in particular I wish that people knew about abortion, per se, but I wish there were some way to convey just how safe, common, simple, and loving abortion is, and just how many people have some experience with abortion in their lives (often many experiences, whether having abortions themselves, or helping friends through abortions, or considering abortion as a possibility for a current or future pregnancy). I think it will take accurate, compassionate portrayals of, and conversations about, abortion across all mediums – entertainment news, TV news, politics, communities, institutions – to make this giant shift. And of course, for that to happen, abortion has to stay legal, and become much more widely accessible than it currently is.

Tanenbaum: What is your favorite TV show or movie with an abortion storyline, and why?

Herold: It’s hard to pick one favorite! There are a few that I really love. Recently, 2021’s Love Life for showing the complex dynamics between a Black protagonist confronting his white sex partner about her racist microagressive comments about having a “cute mixed baby,” and how expectations are different for him as a Black dad. I loved The Letdown’s representation of abortion as a key part of motherhood, parenting, and friendship. CLAWS did an incredible job putting abortion in the context of many people’s lives and centering the experiences of women of color in particular, which we so rarely see on television.I love the compassion and support for Xiomara on Jane the Virgin – watching a daughter support her mom after an abortion was particularly moving. BoJack Horseman’s classic abortion episode is maybe one of my favorite episodes of TV of all time, both for having the most hilarious abortion jokes, at the expense of abortion restrictions, and setting the bar for abortion comedies.

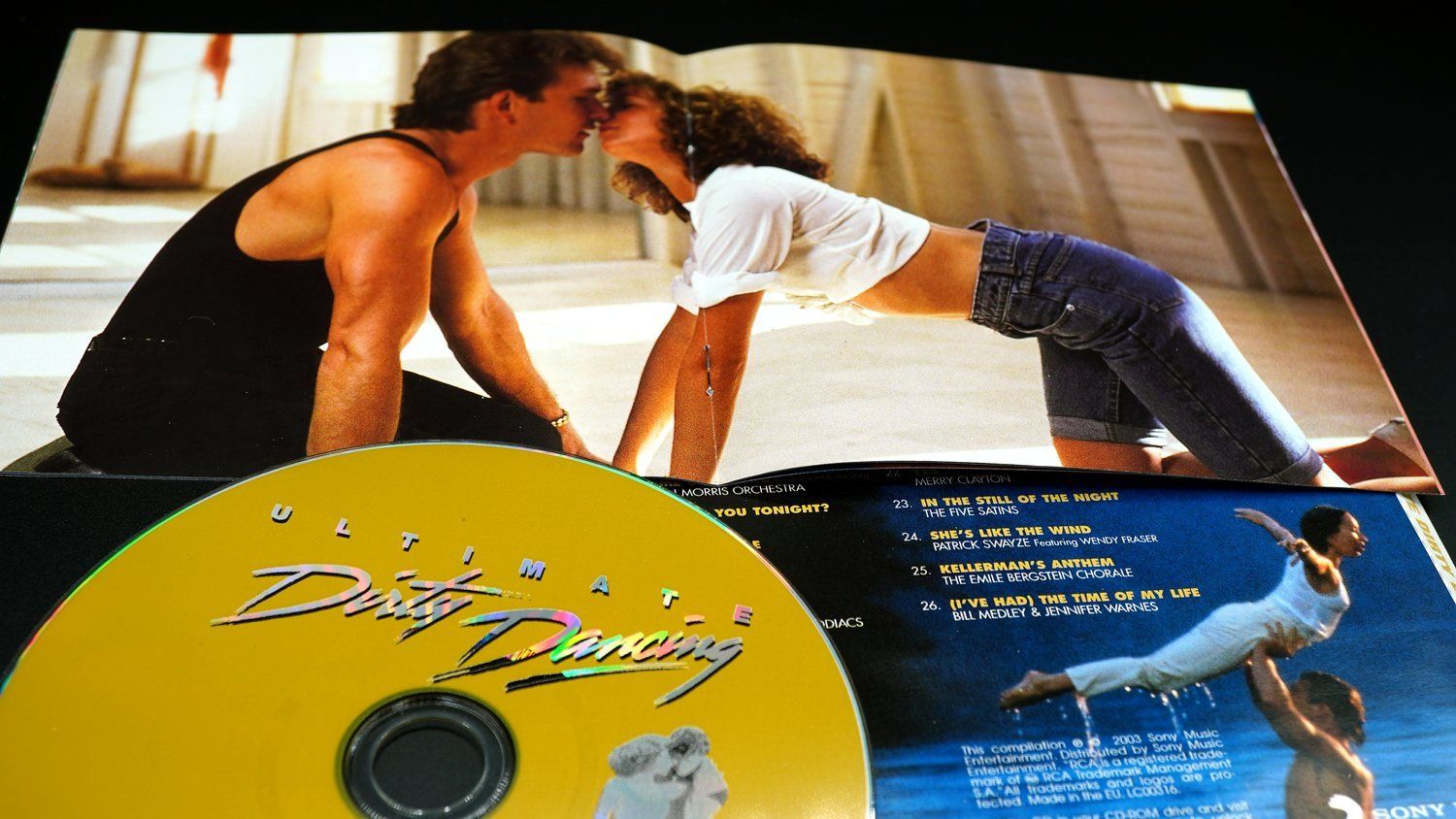

My favorite movie with an abortion plotline is obviously Dirty Dancing, because how could it not be – Patrick Swayze, Jennifer Grey, that soundtrack? Sign me up.

Key takeaway: Knowing the facts about abortion does not necessarily change how someone thinks about abortion. But pop culture may make a difference—so it is essential that narratives reflect the real conditions that actual people experience regarding their reproductive health.

Share Your Story

Have you been sexualized against your will? How did this experience make you feel, and did you push back—or not? Email me at leora@leoratanenbaum.com and let me know if I may quote you—anonymously—in a future issue of this newsletter.