THE LEORA LETTER

Boys will be boys…and girls will be sluts.

November 16, 2021

“Slut,” “hoe,” and “thot” are slippery and subjective terms

that can apply to any girl or woman, regardless of how they dress or behave. I shed light on slut-shaming—how and why assumptions about being “too” sexual are applied, the consequences for women, and the impact on everyone, regardless of gender.

Sexualization Without Consent: Q&A with Cydney Wilson

Colleges across the US mandate sexual consent training for students. Yet there is no evidence that this training reduces the prevalence of coerced and unwanted sex.

We need to rethink what “consent” means and how to talk about it—on campuses and beyond. Let us consider healthy relationships and sexuality more broadly and holistically. And, as always, I must point out that we can’t fully understand these issues unless we account for the role of the sexual double standard and slut-shaming.

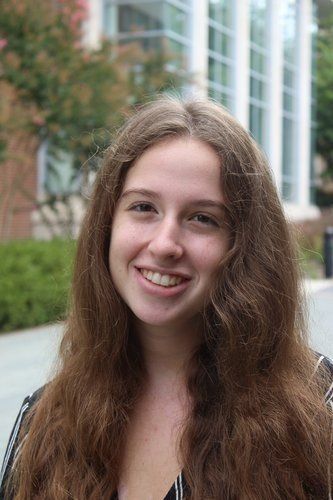

I spoke with Cydney Wilson, a junior at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, who is passionate about keeping students, and everyone, safe from sexual violence and unwanted sexualization. I wanted to know what Cydney, who has offered students peer-to-peer sexual consent resources, thinks about colleges’ approach to consent.

Cydney—who is double-majoring in political science and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and is minoring in Africana Studies—is editor-in-chief of The Muhlenberg Weekly, president of Muhlenberg College Democrats, and vice president of BergVotes. She also is a former student intern and current member of Voices of Strength, which hosts events to educate students on safe, healthy relationships and positive sexual interactions and provides students with a peer, a fellow student, they can turn to if they are looking for information.

Leora Tanenbaum: What led you to become concerned about sexualization without consent?

Cydney Wilson: When I was in the fourth grade, in Irvington, New York, the principal stood outside the school and told girls wearing shorts or skirts, “Arms down by your sides” so that she could decide if our shorts or skirt were too short. So I saw that the sexualization of girls starts at a very young age.

When my sister was in the eighth grade in Irvington Middle School, she was dress-coded for wearing an off-the-shoulder sweater. She was in science class, and her teacher told her to go to the vice principal’s office, and the vice principal told her she had to cover up, so she wore a coat for the rest of the day and was miserable.

I was disgusted. The school essentially sexualized a thirteen-year-old. My sister was devastated. She lost her confidence. She became very aware of the way her body looked to other people and was terrified that whatever she wore, it would make her get called back to the vice principal’s office.

I decided to make it a public issue. I was successful in getting this story covered by the news. It was in the New York Post, Yahoo, and other news outlets.

I emailed my sister's guidance counselor, who had also been my guidance counselor, and said how disappointed I was that they allowed this to happen. And the guidance counselor said, “Well, those are the rules.”

Tanenbaum: What makes dress-coding so harmful?

Wilson: When you are a young woman or someone with minority-gender identity, and you have been sexualized by people who are supposed to be looking out for you, people who are supposed to be educating you, it can lead to you tearing yourself down. It can lead to you seeing yourself as undeserving of respect and equality and being treated like a human being.

And when you feel you have so little value, you are more likely to participate in something you don’t really want to participate in. It can lead you to accept behavior, and not protest it, even if you don’t consent to it.

And if you’re a person of color, you’re dealing with lots of other microaggressions, too.

Tanenbaum: Students of all genders arrive at college having watched their teachers and principals examine girls’ shoulders and the length of their shorts, absorbing the message that this slut-shaming behavior is normal, while girls have not been taught any refusal skills. On the contrary, they have been told, explicitly, that they need to accept the situation. “Those are the rules,” as your guidance counselor said. To my mind, this is a combustible environment that practically invites unwanted or coerced sex.

What is some of the work you have done to try to disrupt this environment?

Wilson: There is mandatory consent training on my campus. I'm also an orientation leader, and I witnessed that when the first-year students attended a mandatory session on healthy relationships and consent, some people never showed up. Some fell asleep. Others were on their phones. And others made rude and nasty comments. While the Department of Prevention Education’s training is comprehensive, it is nearly impossible to cover every important issue in one session, and it is just as difficult to enforce students’ attendance at future events beyond orientation weekend. Additionally, this training shouldn’t be limited to the realm of prevention education; it should be discussed by athletic organizations, Greek organizations, and in academic contexts.

The student group Voices of Strength attempts to go deeper than the college training. Last semester, we hosted events on destigmatizing sexually transmitted infections, pornography, and self-pleasure. We tried to work with Greek-life organizations and the athletic organizations because we have seen that in those environments, issues of sexual assault and lack of consent are particularly prevalent.

Tanenbaum: Slut-shaming is at the center of this environment.

Wilson. Yes. For example, students will catcall female-presenting students or say somebody female-presenting is dressed in a way that shows “just a little too much skin” or that they should “leave a little bit more to the imagination.”

But these conversations need to start many years before a student gets to college. We should talk about consent with children in elementary school. After all, consent is not just about sex. I firmly believe that even young children should have the right to say no—even to family members—to being hugged, if that makes them uncomfortable.

College can be an important turning point for many people and an opportunity for them to learn how to have healthy relationships. But I also want you to remember that many people don't have the privilege to attend college.

Key takeaway: Sexual consent training must start when students are young. Not only are schools failing to provide this training; they are contributing to the problem.

Share Your Story

Have you been sexualized against your will? How did this experience make you feel, and did you push back—or not? Email me at leora@leoratanenbaum.com and let me know if I may quote you—anonymously—in a future issue of this newsletter.