THE LEORA LETTER

Boys will be boys…and girls will be sluts.

September 13, 2021

“Slut,” “hoe,” and “thot” are slippery and subjective terms

that can apply to any girl or woman, regardless of how they dress or behave. I shed light on slut-shaming—how and why assumptions about being “too” sexual are applied, the consequences for women, and the impact on everyone, regardless of gender.

Disapproval of Drinking Women: Q&A with Abigail Riemer

In 2019, the Manhattan district attorney’s office rejected 49 percent of sexual assault cases. Why were half the women dismissed as not credible? Because they had been drinking alcohol, and the attacker was not a stranger.

To try to make sense of drinking women’s perceived lack of credibility, I reached out to Abigail Riemer, PhD, a social psychologist at Carroll University in Waukesha, Wisconsin. Dr. Riemer is the lead author of an important and fascinating 2018 article, “She Looks Like She’d Be an Animal in Bed: Dehumanization of Drinking Women in Social Contexts,” which demonstrates that people express more disapproval of intoxicated women than intoxicated men, and that women who drink are perceived to be less than human.

Abigail Riemer, PhD

Leora Tanenbaum: What is the focus of your work?

Abigail Riemer, PhD: I am a social psychologist, which means that I research how other people influence our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. In my work, I examine the causes and consequences of sexual objectification. I’m interested in how women’s everyday subtle instances of objectification—things like catcalling, comments about one’s appearance, gazes at their sexualized body parts—change the ways they think about themselves and the ways they interact with others.

Tanenbaum: How does sexual objectification connect with sexual violence and slut-shaming?

Riemer: Sexual objectification can manifest in behaviors from the subtle to the extreme—ranging from thinking that a woman’s appearance can speak to her abilities and interests, to staring at a woman’s breasts while they’re talking, to unwanted sexual touching, to rape. Although these instances involve different behaviors, they all share the belief that women are not human, but rather are objects that exist for others’ consumption.

These thoughts lay the foundation for violence; objectified women, like objects, are perceived as capable of being owned and used as tools for others’ sexual goals. Of course, not all men (or women) sexually aggress against women, but these beliefs promote the idea that women exist for men’s sexual use.

Moreover, perceiving women as objects that exist for someone else’s consumption means that we think that women’s sexuality is owned by others—therefore, when women sexually express themselves, slut-shaming is one way in which people can remind women that their value is determined by how they appeal to men.

Tanenbaum: You show that women who drink—but not men—are perceived to violate gender norms. We have seen that this circumstance often leads to victims of sexual violence who had been drinking having their claims dismissed. And your work shows that this circumstance can increase their risk of sexual victimization in the first place. Could you tell us more about this connection?

Riemer: If we were to ask someone to picture someone drinking alcohol, they’d most likely imagine a man, so when a woman drinks, that goes against what we would expect. A woman who drinks is perceived as more willing to have casual sex, more willing to have a one-night stand, and more willing to engage in risky sex.

In my work, we found that because we perceive drinking women as less sexually inhibited, we perceive drinking women—but not drinking men—as more like animals and objects. We see these women as less human—less refined, lacking in self-restraint, and emotionally unresponsive.

Together, perceiving women as more interested in sex and less human sets the foundation for sexual aggression. After all, it is easier to aggress against an animal or an object than an actual human being.

Tanenbaum: Could your findings help disrupt acts of sexual aggression?

Riemer: In past work, we brought men into the lab to explore the connection between alcohol consumption and objectification perpetration. Men were randomly assigned to drink either an alcoholic beverage or a beverage that was prepared to mimic an alcoholic drink, and then we used a device to track their eyes as they viewed images of women in “going-out” attire. We asked the men, while viewing these images, to focus either on the women’s appearance or their personality.

Not surprisingly, when we asked men to focus on women’s appearance, they paid a lot of attention to the women’s bodies and less time to their faces. But, when we asked men who had been drinking to focus on the women’s personality, they spent less time looking at the women’s faces compared to men who were sober—suggesting that they were thinking less about their humanity and more about them as sexual objects.

We also manipulated attributes of the pictured women in terms of how attractive, warm, and competent they appeared. While the bodies of highly attractive women were looked at more than the faces of highly attractive women among all men, intoxicated men spent more time looking at the bodies and less time looking at the faces of women who were low in human attributes—warmth and competence. Because women’s attributes only related to objectification among drunk men, this provides support for the fact that perpetrators, and not targets of unwanted sexual attention, are solely responsible when an assault occurs.

Tanenbaum: Has anything in your research surprised you?

Riemer: Women objectify and dehumanize drinking women too. Perhaps this is because our culture deeply ingrains in us that women are objects meant to be observed and policed. So drinking women are perceived by everyone to lack credibility, which bolsters the myth that they were “asking for it.”

Key takeaway: Cultural attitudes about women, sex, and alcohol predispose us—regardless of our gender—to objectify, dehumanize, and slut-shame drinking women. If they are assaulted, we are primed to blame them and assume they were “asking for it.” We must interrupt this bias and not allow it to obstruct justice for assault victims.

Have you ever been judged harshly for drinking because of your gender? Have you ever judged anyone else for drinking because of their gender? Email me at leora@leoratanenbaum.com and let me know if I may quote you—anonymously—in a future issue of this newsletter.

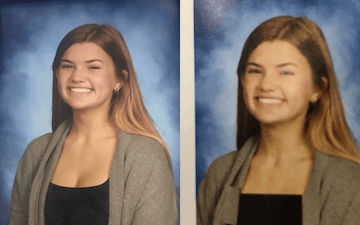

This Bartram Trail High School yearbook photo of student Riley O’Keefe was doctored without her consent.

Share Your Story

Have you been slut-shamed? Dress-coded? If you want to sort out what happened, or you want to consider publicizing your story to raise awareness, please email me at leora@leoratanenbaum.com. I will reach out to you for further discussion. I will not share your story with anyone without your consent.

What Else Is Happening

Learn More

For information on slut-shaming, read I Am Not a Slut: Slut-Shaming in the Age of the Internet, and check out this list of examples in the news.

For information on dress-coding, visit @BeingDressCoded on Instagram.

Author photo: Jahsie Ault